Copernicus wrote three versions of his treatise on the reform of Prussian coinage in the years 1517–26 which have survived in the form of copies and translations.

As has been proved in the course of a thorough analysis of their contents, they are subsequent versions of the same work. The text of the first draft, usually referred to as Meditata, was written in Latin in 1517. This document was produced with Bishop Fabianus Lusianus and members of the cathedral chapter of Warmia in mind and was to support their arguments in debates on monetary reform held during assemblies of the Estates of Royal Prussia (Stany Prus Królewskich). The treatise consisted of two parts.

In the first Copernicus discusses general issues related to the theory of money and formulates inter alia a law of bad money driving out good. In the second he focused on the current monetary situation in Royal Prussia and in particular on the decline in the value of Prussian coinage, enumerating its types and explaining the reasons for the decrease in value of individual coins.

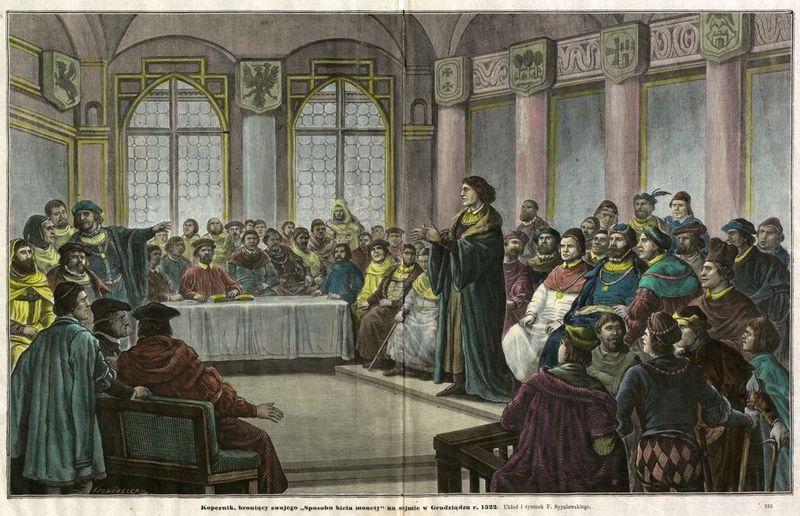

The second version, known from the 16th c. as Modus cudendi monetam (The Way to Strike Coin), was a German translation of the Meditata of 1517. This translation, incidentally abounding in oversimplifications and inaccuracies, was made in 1519 most probably as a document to be presented to the Prussian Assembly attended by the Polish King Sigismund I the Old (Zygmunt I Stary). Copernicus read the German version of his treatise before the Royal Prussian Assembly attended by King Sigismund Is envoys at Grudziądz (Graudenz) on 21 March 1522. Referring to the debate held before his speech, he concluded his presentation with a proposal to mint three Prussian szelągi as an equivalent of one Polish grosz (groshen) and thus to equalize the value of the new Prussian coinage with that issued by the Crown.

The third version of his treatise on money entitled Monete cudende ratio (On the Minting of Coin) survives in three copies and was most probably written before April 1526. This revised version partly based on the text of his 1517 paper, was complemented by a general theory of money with special emphasis placed on the debasement of money as one of the main reasons for the fall of a state.

Copernicus was the first to explain the reason for the decrease in the value of money caused by gold and silver coins being made into an alloy with copper in the minting process. He also presented quite a detailed analysis of the debasement process in relation to Prussian coinage, referring to how the good coinage issued by the Teutonic State gradually decreased in value in the aftermath of the Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg). In this version of his treatise Copernicus also added a new passage in which he stated that the relation between the nominal price (face value) of silver and gold coins should be identical with the price of pure silver and gold. Concluding his paper the author presented the main principles of the monetary reform to be effected in Royal and Ducal Prussia which he summarized in the following six points:

- The reform should be introduced pursuant to a unanimous resolution and preceded by exhaustive deliberations;

- The former coinage should be withdrawn the moment new currency is put into circulation;

- 20 twenty-groshen grzywnas should be made of one pound weight of pure silver bullion - which would lead to equivalence between Prussian and Polish coinage;

- Coins should not be issued in large quantities;

- All kinds of new coins should be put into circulation simultaneously.

An analysis of Copernicus general views on monetary issues show that he was a follower of the metallist theory of money; he saw the source of the value of a coin in its metal content. For him a coin was a marked (stamped) piece of gold or silver which is used as payment for commodities being bought or sold according to the legal tender laws passed by the issuer, namely the state or the ruler. According to Copernicus all kinds of money have their value (valor) and their estimated value (estimatio); while the value of a given coin depends on the amount and quality of the metal bullion of which it is made, its estimatio is its nominal value set by the overall authority in the country.

A good coin should show no difference between its nominal value and the actual value of the material it has been minted from. Copernicus defined different functions for money seeing it as a measure of value, a necessary medium of exchange (for payment or purchase) and of savings. The most important for the advancement of economics, however, is his law of bad money known as Greshams or Copernicus-Greshams Law, already discussed in this paper. Copernicus formulated this law inter alia in the third draft of his treatise on money: when new worse money is introduced while the former better money has remained in circulation, the bad not only infects the good but, as it were, drives it out of circulation.

Copernicus did not limit his economic interests to monetary issues only. Broadening his scope, he contributed greatly to the advancement of economics in general with his method of researching social and economic phenomena by applying a direct cause and effect method of observation drawn from the natural (exact) sciences. In his observations Copernicus followed a holistic approach treating economic life as a unity composed of a multitude of elements. Alongside the importance of monetary stability, he strongly emphasized the significance of trade and agriculture for the economic development of a nation. In his calculation of the bread tariff made in 1531 Copernicus applied the concept of a just price - labour plus other costs. In many respects his views reflected those of mercantilists although it should be clearly emphasized that he did not fully adhere to this doctrine.

English (United Kingdom)

English (United Kingdom)  Polski (PL)

Polski (PL)