Making a few remarks about the way Nicolaus Copernicus wrote, I would like to state from the outset that among the many aspects comprising the subject at hand, I will focus solely on Copernicus' ideological motivations for writing and his formal image as a Latin author.

It is evident that Copernicus had to write in Latin, as it was the language of science during his time. The philological aspect of the astronomer's work was previously addressed by Jerzy Kowalski and Ryszard Gansiniec.

It remains to characterize Copernicus' position as a scholar and writer in relation to the educational and cultural tendencies of his time. Copernicus aspired to be a writer-creator who discovers truths and imparts them to people for moral instruction and the expansion of their knowledge. These were precisely the reasons for undertaking literary work in various fields that Copernicus mentioned in the introduction to his translation of Theophilus' Letters and referred to in the dedicatory letter to his work, De revolutionibus. It is extremely significant and highly characteristic of Copernicus' disposition that he did not seek personal fame through his own creative work or the privileges that accompany such fame. During a period marked by the greatest intensity of authorial ambitions, represented by Renaissance writers who demanded high rewards for their works during their lifetime and long-lasting fame after death, Copernicus remained utterly indifferent to seeking public acclaim for his own creativity. This does not mean that he did not derive profound inner satisfaction from his work. It is precisely this satisfaction that he mentioned in the dedicatory letter of De revolutionibus. Copernicus had the joyful awareness that while other astronomers focused only on details and described mere fragments of the celestial image, he, as the first, discovered the astonishing symmetry of the universe as a whole and the true means by which harmony is maintained within this universe.

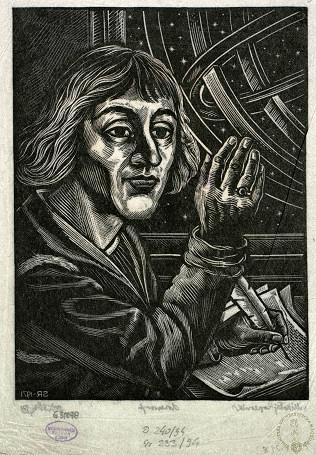

he woodcut by Stanisław Rolicz from 1971. University Library in Toruń

he woodcut by Stanisław Rolicz from 1971. University Library in Toruń

Where did Copernicus learn Latin and the Latin style? He began his education at the parish school of St. John's Church in Toruń, where he received his initial training. During his university studies from 1491 to 1495 in Kraków, he acquired an excellent command of Latin. Latin was the language of instruction and, to some extent, the language of communication among students from various European countries. It is also known that during his studies in Kraków, Copernicus further improved his knowledge of Latin through the reading of specialized works, such as the Latin translation of Euclid's Geometry, as well as some works by Aristotle and Averroes. It can be assumed that Copernicus came to Kraków primarily to pursue studies in mathematics and astronomy.

In the late 15th century, the University of Kraków was indeed an important international center for such studies. In 1496, Copernicus went to Bologna to pursue legal studies. These studies were intended to have a practical perspective, as envisioned by their sponsor, Bishop Łukasz Watzenrode of Warmia, who was Copernicus' uncle. They were focused on a future career in the Warmian bishop's curia and the Frombork chapter. This career, limited to the position of canon in the chapter, would later burden Copernicus with numerous administrative duties that he had to combine with his own astronomical work and research. In 1500, he completed a legal internship in Roman curia, specializing in canon law. In the first half of 1501, Copernicus returned to Warmia, but in August of that year, he embarked on medical studies in Padua. In 1503, he obtained a doctorate in canon law from Ferrara, thereby acquiring the necessary education for fulfilling the duties of a canon in the cathedral chapter.

We briefly traced Copernicus' university itinerary because it was in Padua that he began learning Greek in the Byzantine Koine dialect. His knowledge of this language, necessary for studying the works of Greek astronomers in their original form, also had an influence on his Latin writings. There was a Greek language lecturership in Padua, but it can be assumed that Copernicus learned the language independently. Surviving among his collections, now held in Uppsala, are educational aids in the form of a Greek grammar and a Greek-Latin dictionary. Therefore, he learned Greek through the intermediary of Latin, which he already had an excellent command of at that time.

To answer the two questions posed at the beginning regarding Copernicus' ideological motivation for his work and his style of expression (along with the additional question about the sources and quotations from foreign authors found in Copernicus' works - in his time, the number of citations from foreign authors contributed, among other things, to the value of a work), we must first turn to the texts of the astronomer and then consider the numerous findings from Copernicus researchers.

Around the year 1509, works emerged that provided compelling evidence of Copernicus' writing and even literary skills. It was during this time that Copernicus wrote the Outline of Astronomy (known as the Commentariolus). This small treatise was not published by the author but was only circulated in a small number of handwritten copies. It is highly significant as the first written formulation of the heliocentric theory. The treatise is also interesting from a linguistic and formal standpoint. Copernicus proved to be a writer who could maximally generalize immensely complex issues and, using only narrative description, present them synthetically. As befits a scientific text from the early 16th century, the Commentariolus was written in precise and terminologically accurate Latin. Copernicus demonstrated himself to be an excellent Latin scholar and, at the same time, a scientific writer capable of methodically presenting his theses. Copernicus was not unfamiliar with the principle of contemporary pedagogy, which can be summed up in the formula: bene qui disposuit bene docet (one who arranges the content of a lecture well teaches effectively).

Indeed, the treatise Commentariolus had a very structured and correct arrangement, in which the author first presented the views of his predecessors on the discussed subject, then presented his own claims and their justifications, and finally drew conclusions in the summary. Commentariolus thus became, in terms of content, the beginning of modern scientific literature and an example of Copernicus' scientific statements characterized by concreteness and precision.

In 1509, a text completely unrelated to Copernicus' astronomical interests was published in Krakow. It was his Latin translation from Greek of the Letters on Etiquette, Rural Life, and Love by the Byzantine writer Theophylact Simocatta. In a carefully stylized Latin preface addressed to Bishop Lucas Watzenrode, Copernicus presented his work as an expression of gratitude to his uncle, the patron and sponsor of his years of university studies, and also as a desire to provide readers who only knew Latin with a morally, socially, and culturally valuable work from Greek literature. This work dealt with topics such as the education of youth, rural management, and neighborly relations, and as Copernicus emphasized, it combined elements of sadness, seriousness, and joy. The value of this reading, according to the translator, lies not only in its singular theme but in showcasing the diversity of situations that occur in a person's life. In this way, Copernicus aims to present himself as a writer-creator who shares the fruits of his work with readers in need of both moral guidance and entertainment.

The translation of Theophylact Simocatta's Letters was a youthful publication by Copernicus that went far beyond his scientific interests. Researchers of the Letters (Kowalski, R. Gansiniec) have noted that Copernicus had limited knowledge of Greek when he worked on the translation. The translator omitted many words and parts of sentences in the translation that he did not understand or deliberately wanted to simplify the meaning of his own translation. The Latin of the translation, although free of errors, is described by the aforementioned researchers as "plain and unadorned," presenting a "down-to-earth image." This situation can be easily justified. While translating a work belonging to belles-lettres literature, Copernicus primarily aimed to make the praise of important social virtues such as diligence, prudence, honesty, and friendship contained in the Letters accessible. He did not strive to be (nor was he) a writer who captivated readers with elaborate stylistic ornamentation and language. Already in this text, namely the translation of the Letters, Copernicus presented himself as a Latin writer who, apart from exceptional cases (official dedications addressed to prominent individuals), avoided a rhetorical, ornamental form of expression intended to evoke emotions. This attitude is further intensified in Copernicus' other works.

The known private and official correspondence of Copernicus, now published, stands out in its linguistic layer for its correctness of Latin syntax, carefully chosen vocabulary appropriate to the circumstances, and conciseness. The letters written by Copernicus were, of course, far from incorporating all the nuances and embellishments recommended by Renaissance epistolography. However, what characterized his correspondence, and was most important to Copernicus, was clarity and unambiguous expression, consistency, orderly arrangement, and logical coherence.

Regarding Copernicus' language and style, it is necessary to consider his other works as well. One such work is a small Latin treatise called Monetae cudendae ratio, dating from 1523, which was written during the Polish-Prussian monetary reform. The treatise was not published by the author and remained in its original handwritten form in the archives of the chapter in Frombork. It was taken by the Swedes along with other books during the Polish-Swedish war in 1626. It was returned to the State Archive in Königsberg (Królewiec) in the early 19th century and soon identified and published by Feliks Bętkowski in Pamiętnik Warszawski in 1816. Since then, this work by Copernicus has been circulating in the scientific community and has been the subject of research and comparisons as it pertains to an important aspect of social economy - exchange, more precisely the instrument of exchange, namely money. The text is linguistically correct and stylistically "unadorned" because it deals with very concrete matters. In this work, Copernicus employed the language of science but did so in such a way that readers had no doubts about the author's views, thanks to precise terminology and transparent construction.

Copernicus' main work, "De revolutionibus," as the most extensive text in his body of work, also provides the greatest opportunities to observe his language, style, and composition. This work will also serve us to determine Copernicus' motivations for pursuing his scientific work and what science (contained in the seven liberal arts) can mean for humanity.

In general, it can be said that in this work, Copernicus generally avoids stylistic embellishments and adheres to the composition appropriate for classical exposition. Of course, consciously made exceptions do occur. The work "De revolutionibus" had a Greek warning inscribed on the title page, stating that no one should embark on reading it without knowledge of geometry. However, the composition of the work is such that educated individuals, who may not necessarily be knowledgeable in geometry, could read and understand the first book. The subsequent books, from the second to the sixth, differ completely in character from the first book, as they contain almost exclusively detailed geometric and numerical representations (from the perspective of the heliocentric theory) of the apparent and real motion of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars. Copernicus employed a certain writing technique, using two styles or rather two orders of discourse: the one from the first book, which aimed to introduce and familiarize readers with the heliocentric theory in a preliminary (and accessible) manner, and the other, a strictly scientific order, which Joachim Rheticus referred to as the style of geometers. In both compositional orders, Copernicus consistently adhered to clarity and simplicity of expression.

In general, it can be said that in this work, Copernicus generally avoids stylistic embellishments and adheres to the composition appropriate for classical exposition. Of course, consciously made exceptions do occur. The work "De revolutionibus" had a Greek warning inscribed on the title page, stating that no one should embark on reading it without knowledge of geometry. However, the composition of the work is such that educated individuals, who may not necessarily be knowledgeable in geometry, could read and understand the first book. The subsequent books, from the second to the sixth, differ completely in character from the first book, as they contain almost exclusively detailed geometric and numerical representations (from the perspective of the heliocentric theory) of the apparent and real motion of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars. Copernicus employed a certain writing technique, using two styles or rather two orders of discourse: the one from the first book, which aimed to introduce and familiarize readers with the heliocentric theory in a preliminary (and accessible) manner, and the other, a strictly scientific order, which Joachim Rheticus referred to as the style of geometers. In both compositional orders, Copernicus consistently adhered to clarity and simplicity of expression.

Speaking of "ordinary" readers, they need to be distinguished from professional astronomers, for whom, in essence, Copernicus wrote his work—a mathematical work, to be precise. Thus, the first book, although written in a clear and narrative manner, with only a few geometric diagrams, was not and could not be a popular exposition on the structure of the universe. There are many concepts and generalizations derived from antiquity that can only be understood in the context of the history of scientific thought. This applies to strictly astronomical concepts as well as philosophical concepts (which will be discussed below). It should be noted that the first book was easier to understand in the past, by readers in the 16th, 17th, and even 18th centuries, than it is for contemporary readers, whose knowledge of the heavens is purely book-based and who have never seen, for example, the stars of the Eagle or the Little Dog (mentioned in the sixth chapter of the first book). And the people who lived in Copernicus's time and even those who lived later, and whose civilization did not cut off their visual contact with astronomical phenomena, experienced the described by Copernicus variable motion of planets and configurations of stars as part of the natural backdrop of their daily lives. Will a resident of a large city today see as many stars on a clear night as Copernicus did, and can they echo his sentiment, "What is more beautiful than the sky?" Despite all the stylistic conveniences, when reading the first book, one clearly feels the distance of centuries and the concept of an astronomical work.

To summarize the previous remarks on Copernicus's Latin style, it is necessary to dwell on a completely exceptional text. I am referring to the dedication of the work "De revolutionibus" to Pope Paul III. The text was exceptional because, in addressing the Pope, Copernicus wrote it in a formal, rhetorical style (instead of the concise, factual style usually employed), adding quotations and stylistic embellishments. In the dedication, there are many long sentences with complex, chain-like structures. The use of such sentences was recommended by Renaissance theory of rhetoric, but Copernicus hardly ever employed this kind of style. In the dedication, he departed from this principle.

Let us examine two sentences from the dedication, long and elaborate, yet also very substantive. "And I have no doubt that talented and capable mathematicians will completely agree with me, provided that they fulfill what this science [in the Latin text, philosophia] primarily requires, namely, that they willingly and thoroughly comprehend and ponder everything that I present in this work as evidence for my assertions. And in order to demonstrate to both the learned and the unlearned that I do not shy away from any criticism, I preferred to dedicate these fruits of arduous labor to Your Holiness rather than anyone else, precisely because even in this remote corner of the earth where I reside, you are recognized as the most eminent, both due to your hierarchical dignity and your love for all sciences, including mathematics" (translated by Mieczysław Brożek). It is noteworthy that these sentences also caught the attention of the researcher of Copernicus's language and style, Jerzy Kowalski. He considered them representative and characterized them as follows: "[...] it is not an inaccessible style, nor an obtrusive style, but nobly restrained, yet learned and artistic; it is a lively style adorned only by the beauty of life, neither mummified nor embellished. If there is any elegantia, not attached to words and formulas but expressed in a worthy and noble attitude, so to speak, of expressions, in their serious gaze, graceful structure, and harmonious sound, in some internal linguistic dignity that contains a bit of humanity and a bit of a statue, if there is any elegantia in all of this, then there is elegantia in Copernicus's prose."

One of the characteristics of Renaissance style of expression was the use of quotations from other authors. They were meant to confirm the writer's arguments and also (and above all) demonstrate his erudition and scholarship. In Copernicus's works, quotations do appear, but far less frequently compared to other contemporary Latin scientific writers. Particularly, Copernicus included a significant number of quotations in ceremonial and specially stylized texts, such as dedications. He concluded the dedication of his translation of Symocatta's Letters with a quote taken from Ovid (Fasti, I,18), which—referring to Bishop Lucas Watzenrode—reads: Ingenium vultu statque cadatque tuo (Creative genius stands and falls under your gaze). A kind of quotation is the commonly known Platonic warning, written in Greek on the title page of "De revolutionibus": Ageometretos udejs ejsito (Let no one ignorant of geometry enter).

Several quotations can be found in the dedication of the work "De revolutionibus." In that passage, Copernicus referred to an apocryphal letter from the Pythagorean Lysis to Hipparchus, seemingly illustrating his long hesitation to publish his work on the heliocentric theory. When he mentioned that the work had remained hidden not only for the proverbial nine years but much longer, namely, for four nine-year periods, he alluded to Horace's recommendation (Ars Poetica 388-389) that an author should keep his work for nine years, constantly revising and improving it. Copernicus then mentioned unnamed mathematicians who tangled themselves in contradictions in their research and were unable even to determine and calculate the constant value of the tropical year, let alone explain the observed motions and rotations of celestial bodies or the entire mechanism of the world. However, Copernicus did mention by name those ancient authors who made references to Greek philosophers proposing the motion of the Earth. He acknowledged that he found a mention of Nicetas by Cicero (Academica Priora II), who believed in the motion of the Earth. Copernicus even included a quote from Plutarch, without specifying the source, which was a common practice in the 16th century, regarding three other Greek philosophers - Philolaus, Heraclides of Pontus, and the Pythagorean Ecphantus - who accepted the rotational motion of the Earth. This important quote, along with the mention of Nicetas by Cicero, prompted Copernicus to contemplate the possibility of the Earth's motion and is from Plutarch's work "De placitis philosophorum II."

The few scattered references to Ptolemy's "Almagest" throughout all the books of "De revolutionibus" are rather obvious. Researchers have identified traces of Homer's reading (Iliad XVIII, 486) and Hesiod (Works and Days, 610) in the second book. In the first book, Copernicus mentioned Plato's name five times, referred to Sophocles' Electra, Euclid, and Aristotle. There are so few of these quotations that one can echo Alexander Birkenmajer's observation that Copernicus used quotations very sparingly. One longer quotation consisting of two lines, "When we, together with the Earth, revolve, the Sun and the Moon pass us by. The stars, however, return to us alternately and then recede," raises doubts among researchers as to whether it originated from Copernicus or if it is a paraphrase of verses by other authors who described this phenomenon.

Copernicus, in comparison to other scientific writers of his time, cited very little. However, he was well-read and if a precise and impressive quote was needed, he could even delve into highly specialized and obscure literature. In the tenth chapter of the first book, Copernicus reminded us that the Sun is referred to as the "visible god Trismegistos." Aleksander Birkenmajer, who analyzed this quote, stated that Copernicus read this epithet of the Sun in a treatise by Hermes Trismegistos entitled Poimandres, translated into Latin in 1468 by Marsilius Ficinus and titled Liber de Potestate et Sapientia Dei.

According to the announced plan, we should now address the question of what can be said about the motivations that led Copernicus to undertake fundamental scientific research and what educational significance he attributed to science. The general statement made by Aleksander Birkenmajer, that Copernicus was guided by a profound love of learning in his work, particularly in the field of astronomy, and believed that science moralizes people, should be further explored and extensively documented.

When Copernicus, in 1509, attempted to justify his choice of the work in the dedication of the Letters of Theophylactus Simocatta, he emphasized its moral values and specificity, which could convince the readers. "We do not see mere letters in them," wrote Copernicus in the dedication, "but rather principles and regulations shaping human life, as evidenced by their conciseness, for I have selected from various authors what is most concise and fruitful" (translated by Jan Parandowski). In this dedication, we can already discern the accents that will be visible in Copernicus' further work. Shaping human life, which means educating individuals through books written and arranged in the proper manner, concretely, objectively, and concisely, manifested the humanitas of Copernicus. It involved assisting people in attaining a higher level of ethics and knowledge. Copernicus embraced this kind of message through his presumed identification with the idea of interhuman assistance and the "giving of faithful advice to those who seek it." Such an idea was advocated by the knowledge encompassed within the seven liberal arts, which aimed to provide individuals with wisdom and moral virtue.

Let us consider Copernicus' own statements on this matter. In light of his remarks, Copernicus emerges as a writer-creator and scholar who, despite internal reservations and awareness of the (Pythagorean) tradition of concealing his knowledge, desires to share the results of his research and the fruits of his talent with readers eager for knowledge and profound moral instruction. Above all, he aspires to be the scholar-writer who uncovers truths and imparts them to people. "And since the task of all noble sciences," wrote Copernicus in the first chapter of Book One of De revolutionibus, "is to divert man from evil and direct his mind toward greater perfection, this science, in addition to the immeasurable delight of the intellect, can accomplish this to a fuller extent than others" (translated by Mieczysław Brożek). It is understandable that Copernicus considered astronomy the most perfect science in every respect among all the liberal arts. Copernicus expressed the same idea in slightly different words at the very beginning of Book One: "Among the numerous and diverse arts and sciences that arouse our passion and serve as nourishment for human minds, it is, in my opinion, above all necessary to devote oneself with the greatest zeal to those that revolve around the most beautiful and worthy things. And such are the sciences that deal with the wondrous movements in the universe, the courses of the stars, their sizes and distances, their rising and setting, and the causes of all other phenomena in the sky, ultimately explaining the entire structure of the world" (translated by Mieczysław Brożek).

The Renaissance principle proclaimed in humanist circles, that one must assist others in acquiring knowledge because there is an enlightening and moralizing natural light in learning, namely natural reason, found a certain echo in Copernicus' words (in the dedication to the Pope) that the urgings of his friends overcame his fear of publishing the work, and he decided to dedicate it for the common use of those engaged in mathematical studies.

The above text appeared in the "Quarterly Journal of the History of Science and Technology," Vol. 53: 2008, No. 2-3, pp. 51-60.

English (United Kingdom)

English (United Kingdom)  Polski (PL)

Polski (PL)